Production Problems Arise as Effects of Warm Winter Linger Throughout Growing Season

Aborted ‘Pawnee’ fruit prior to drop shows visible stains on shuck from endosperm leaking from within. (Photo by Lenny Wells)

The first of these effects to show up on the crop was seen in ‘Pawnee’ around the end of June and the first week of July. It is common for ‘Pawnee’ to shed a few nuts around that time of year, but this year’s drop was heavier than normal. Depending upon location, many ‘Pawnee’ orchards dropped 30 to 70 percent of their nuts, with the percent increasing from low to high as you moved southward in Georgia. In addition, orchards of solid blocks of ‘Pawnee’ and no to few pollinators tended to have a heavier drop. Many of the ‘Pawnee’ nuts that dropped showed staining on the shuck. This results from staining of the shuck from within by the liquid endosperm leaking out, much as you see with water stage fruit split, which occurs later in the season.

While many growers think that drop resulting from pollination issues happens only early in the season—much of it normally does—pecans actually undergo four separate and distinct fruit drops during the growing season, most of which are related to pollination problems. Usually, most of these drops are fairly minimal so they often go unnoticed or they are of little consequence.

Perhaps it will be easier to explain all this with a more detailed description of what happens during pollination. Each pecan pollen grain contains three nuclei. After one nuclei germinates and forms the pollen tube, another travels down the pollen tube and unites with other cells in the ovary. This will develop into the nutritive endosperm, which is used as food for the developing embryo. The third nucleus travels down the pollen tube and fuses with the egg to form a zygote, or fertilized egg. From this zygote, develops the embryo and cotyledons, which make up the pecan kernel.

The process from pollination to fertilization takes two to six days for pecan, which is much longer than most plants, which require only a few hours. Following fertilization, the fruit will develop over 80 to 90 days until it reaches full size toward the end of July. During the first half of the growing season, the endosperm develops very rapidly. From mid-June to mid-August, the endosperm is rich in growth substances and sugars, and can be compared to coconut milk.

The integument (seed coat) grows and expands very slowly for the first 50 to 70 days or so after pollination. This growth rate increases in mid-July as the integument expands into the fissures of the packing tissue, forcing them against the surrounding walls. The liquid endosperm exerts pressure, which forces the integument into all available space within the shell. Thirty days later, as it reaches full size, the integument becomes the seed coat, enclosing the growing embryo. So as you can see, the process of pollination/fertilization is complicated and can go wrong at several points. This is why pecans and other plants produce so much pollen.

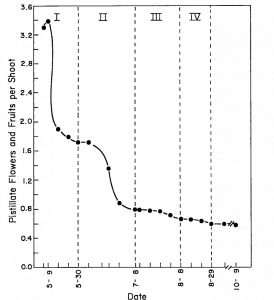

This graph from Sparks and Madden, 1985 shows the third drop of aborted pistillate flowers and fruit in ‘Desirable’ pecan, which aligns with the drop for ‘Pawnee.’

‘Pawnee’ is about a month ahead of most of our other varieties, so the late June and early July drop on this variety would coincide with the third drop in the graph shown (which is based on ‘Desirable’ from work by Sparks and Madden, 1985). This drop occurs just before rapid fruit expansion and is due to the failure of that endosperm, which feeds the nut, to develop properly. This explains the leaking of the endosperm from within, which stained the shucks. The timing of the ‘Pawnee’ drop we saw is known to be accentuated by self-pollination, which was likely higher as a result of the warm winter effects on bud break and subsequently pollination. This also explains why orchards of solid blocks tended to have more drop than those with good pollinator populations. A fourth drop also occurs later in the season, caused by abnormal embryo development.

The most noticeable effect of the warm winter this year could be seen in the extremely late bud break we saw on ‘Stuart’ in areas with low chill. This was the first sign that something was out of place. For many fruit trees, once buds have entered dormancy, they will be tolerant to temperatures below freezing and will not grow in response to mid-winter warm spells. These buds remain dormant until they have accumulated sufficient chilling units (CU) of cold weather. When enough chilling accumulates, the buds are ready to grow in response to warm temperatures. As long as there have been enough CUs the flower and leaf buds develop normally. If the buds do not receive sufficient chilling temperatures during winter to completely release dormancy, trees will develop various physiological symptoms associated with insufficient chilling.

Chilling requirements for pecan vary by cultivar. It is reported that 300 to 500 chill hours are required for ‘Desirable,’ ‘Mahan,’ ‘Success’ and ‘Schley,’ while ‘Stuart’ reportedly requires from 600 to 1000 hours. Chilling hours for Byron, Georgia this year (just below Macon) were 574, which is over 300 hours less than the previous year. Going south, the chill hours were 565, 418 and 264 for Cordele, Albany and Valdosta, respectively.

The actual chilling requirement for pecans also varies with fall temperatures. If trees are exposed to cooler fall temperatures (less than 34 degrees Fahrenheit) the intensity of the bud’s rest is greater and the number of chill hours required for bud break increases. But the colder the winter, the fewer the heat units in spring required to start bud break. Heat units in spring strongly influence bud break and drive the progression of the crop’s maturity. So, with a cold winter and warm spring, you can actually get a pretty early bud break.

We had a warm fall; therefore, the intensity of the bud’s rest was weak and the number of winter chill hours required for bud break was likely lower. If you looked around at the edges of fields and in the woods in mid to late February you saw red maples, red buds, and oaks budding out. Azaleas were blooming in the yards. And yes, some pecans were even budding out already.

Because bud break tends to be so sporadic, staggered and non-uniform when you have low chill hours, the synchronization of female flowers with male flowers from the pollinators was likely off, leading to poor nut set and poor quality. The nut drop we saw from excessive self-pollination on ‘Pawnee’ was one effect of this condition.

Most of our ‘Pawnee’ trees had a heavy crop load. Those that only dropped about 30 percent of their nuts still have a good crop on them and the drop probably helped them more than hurt them. These trees should be able to produce better quality and have a better chance of a return crop. Those that had a heavier drop, of course, have their yield potential for this year reduced, but there was nothing growers could do about that.

My concern at this point is that we will see this on other varieties as well. By the time you read this, we will likely know the answer to that question. In addition to heavier fruit drops, we also have to consider the potential for any quality issues like embryo rot and stick tights that may arise from poor pollination, which may not show up until harvest time.