Wild Pigs: Another Problem for Pecan Producers

Photo by Robb Mattson, Noble Research Institute

Below, we highlight some of the latest research on how wild pigs use agricultural landscapes and how damage can affect economic viability (for instance, how wild pig damage influences pecan harvest efficiency).

What Are Wild Pigs?

Wild pigs are an invasive, non-native species in the United States, known to cause extensive amounts of damage to agricultural operations. In 2016, the United States Department of Agriculture reported a conservative estimate of $2.5 billion annually in damage. Wild pigs are a challenging pest to manage due to factors such as high reproduction and survival, the ability to adapt to altered environments, and the absence of natural predators.

Because of wild pigs, agricultural producers face many challenges that can reduce their economic viability. Agricultural products such as grains, fruits and nut crops often offer an easily accessible food source for wild pigs, which reduces total production yield.

In addition to direct consumption, other wild pig activities, such as rooting, wallowing, digging and trampling, can compound losses to producers by reducing yields and affecting the ability to efficiently harvest agricultural products.

Stephen Webb, Ph.D., collars a captured wild pig with a GPS tracking collar in order to follow its movements and behavior for the study at the Red River Farm in Burneyville, Oklahoma. (Photo by Rob Mattson/Noble Research Institute)

Wild Pigs and Pecans

Across the southern United States, where some of the highest densities of wild pigs occur, pecans are a specialty crop readily grown in conjunction with other farming and ranching operations. Pecans are one of the most popular specialty crops produced in Oklahoma. In 2017, Oklahoma was the fifth largest pecan-producing state, producing 14 million pounds of pecans, valued at approximately $24 million.

Geographical overlap of wild pigs and pecans likely leads to pecan consumption by wild pigs because the nuts offer a high caloric, abundant food source at a time of year when food is limited.

For these reasons, the Noble Research Institute and Oklahoma State University initiated a study to investigate wild pig habitat use, ecology and damage within agricultural landscapes where pecans are actively grown and harvested.

The Study

This study took place on the Noble Research Institute’s Red River Farm in Love County, Oklahoma. The Red River Farm is a 3,252-acre demonstration and research farm situated along the northern edge of the Red River. This study area offers an opportunity to investigate the relationships between wild pigs and active pecan growing operations as well as other land uses such as cropland and native rangeland and pasture for grazing cattle.

We captured wild pigs using BoarBuster suspended traps. Our goal was to capture two adult female (sows) wild pigs per sounder (group of pigs) and fit them with GPS tracking collars. These collars allowed two-way communication between the collar and user so researchers could download the data every five to six hours. As defined in the Oklahoma Feral Swine Control Act, it is illegal to release any wild pig unless fitting the pig with a radio collar. Under the “Judas pig” provision, we fitted wild pigs with GPS collars so we could later track them down to assist with population control efforts.

Findings

- Sixteen sows were captured from a total of eight sounders in 2016.

- Thirteen sows were captured from a total of nine sounders in 2017.

- Sow survival was high with only 1 of 29 sows being harvested.

- Average litter size of pregnant sows was 5.3 (range equals 2 to 9)

- Average home range size (76 days; Oct. 14, 2016 to Dec. 28, 2016) was 564 acres (range equals112 to 1,204 acres)

- Average home range size (69 days; Oct. 13, 2017 to 20, 2017) was 350 acres (range equals 73 to 1,223 acres)

- Average sounder home range size (with multiple sows per sounder) was 659 acres

- In 2016, 11 of the 16 collared pigs crossed the Red River 80 times (range equals 2 to 11 crossings).

- Female wild pigs showed a strong liking for riparian vegetation communities and pecan orchards.

- Sows also used areas closer to water sources, including streams, rivers and ponds.

- Sows also used crop fields, rangeland and forested areas, but under a narrow range of conditions.

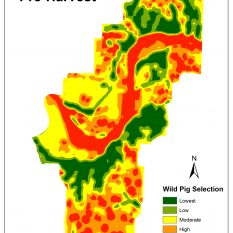

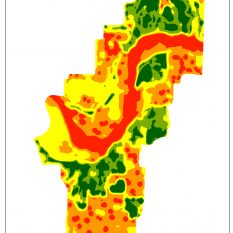

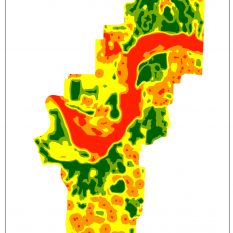

- The three maps show areas consistently used by sows (in red) across the pre-harvest (two weeks before pecan harvest), harvest (four weeks of harvesting), and post-harvest (two weeks after pecan harvest) periods. You can see areas of greatest use (in red and orange) to least use (green shades), and how the patterns change across periods.

- At the conclusion of each study period, all collared wild pigs and their sounder mates were targeted for collection either using very high frequency (VHF) tracking or recapture with the BoarBuster trap.

Takeaways and Next Steps

In general, wild pigs are very adaptable, using a wide range of habitat types. However, sows showed very strong selection for riparian areas, pecan orchards and proximity to available water.

The relationships between wild pigs and their habitat were incorporated into a geographic information system to map the areas most used by sows and their sounders as a way to prioritize areas for population control. The predicted maps are similar to hot spot maps where we are able to identify where pigs spend most of their time.

We also can use the social nature of pigs to our advantage for control efforts. Sows within the same sounder tended to always stay within their sounder, meaning individual pigs did not move among sounders. Sows also have relatively small home ranges, and when this information is combined with hot spot mapping, we can fine-tune trap site locations to have a greater chance of attracting the whole sounder to a bait site.

An uncollared wild pig and its sounder rush around a BoarBuster trap, while researchers prepare to place a GPS tracking collar onto the pigs. (Photo courtesy of the Noble Research Institute)

Control Challenges

Despite what we learned about wild pigs that we can use to our advantage, there still are many factors that make population control difficult. Survival is high, at least for sows. That is a problem since adult sows are the most reproductive age class, having an average litter size of more than five piglets and sometimes as many as nine. Sows also can have multiple litters per year.

Also making control efforts difficult, at least on our study site, is the fact that the Red River runs along the southern border of the property. The habitats associated with the river offer an ideal habitat and security cover for wild pigs. The river itself also acts like a corridor where pigs move up and down the river, meaning that a lot of transient pigs also use the area.

Future Research and Tools

There is always something new to learn about these creatures, so Noble is continuing its efforts into wild pig control and research.

Current projects are examining male (boar) ecology, movement, habitat use and survival, which may differ quite dramatically from that of sows.

On Noble’s Oswalt Ranch, cattle, white-tailed deer and wild pigs are fitted with GPS collars to learn more about their interactions such as disease spread, differences in habitat use and potential negative effects of wild pigs on the behavior of other species, particularly native wildlife.

We are also developing online tools to help landowners track the success of their control programs. Landowners will be able to enter simple information to estimate the age of wild pigs, which then will be used with other information to estimate survival rates and population size. Changes in population size can be used as an indicator of the success (or lack thereof) of population control programs.